And the angels wouldn't help you, because they've all gone away

"Picnic at Hanging Rock" (1975), "Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me" (1992), and "The Virgin Suicides" (1999)

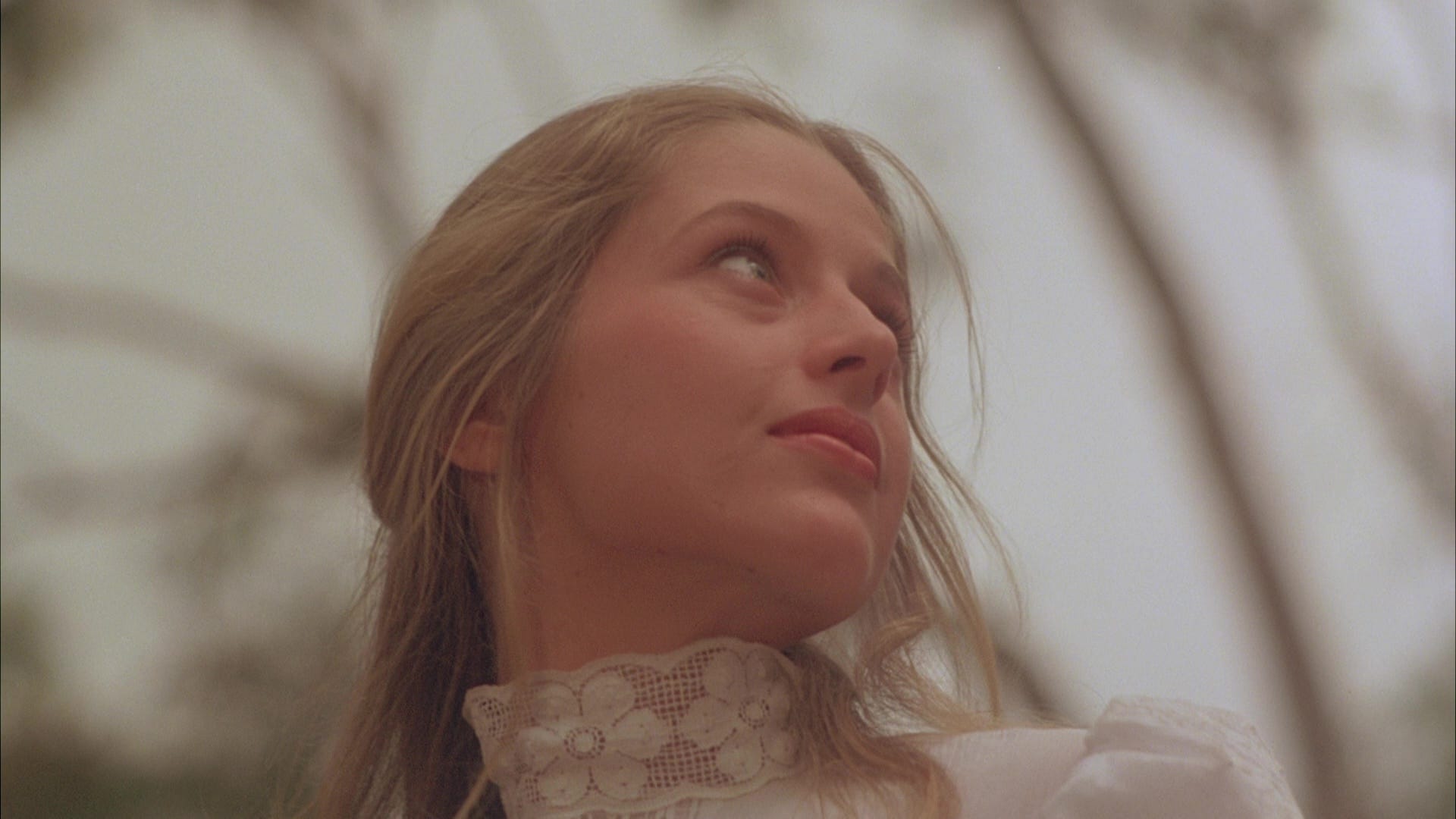

I recently saw the 4K restoration of Peter Weir’s 1975 film Picnic at Hanging Rock at IFC Center, which was gorgeous. Considered one of the great Australian films, it’s a chilling, potentially supernatural mystery about three schoolgirls who vanish into the outback on Valentine’s Day, 1900.

It was immediately clear why this film and The Virgin Suicides, Sofia Coppola’s debut film, are often compared: both are languid and voyeuristic, and there’s similar plot points, including a Greek chorus of local boys who spy on the girls and love them blindly, and a fatal fall from an open bedroom window. With its fluttering Victorian garments, dream-like dissolves, and sun-baked color palette, Picnic is the movie that launched a thousand Rookie Mag photoshoots.

But on my first watch, Picnic reminded me as much—if not more—of the TV show Twin Peaks and its prequel film, Fire Walk With Me. I did some Googling, but found no evidence that creators David Lynch or Mark Frost were influenced by the 1975 film. (It seems they were more inspired by their research for a failed project about Marilyn Monroe—another tragic, misunderstood blonde.)

Since this newsletter is about putting films into conversation and seeing what emerges, these three felt like the perfect place to start, especially on Valentine’s Day—the date of the schoolgirls’ disappearance in Picnic.

(Also please note this newsletter will never be this long again… this one is kind of like when you turn on an old faucet after a long time, and you have to let all the rusty water out first)

“This is the girl”

TW: suicide, self-harm, SA, CSA

Miranda St. Clare, Laura Palmer, Lux Lisbon. Their names almost sound like an incantation: fitting for characters who seemed to belong to another realm even while they were alive.

Miranda is the ethereal ringleader of three girls who disappear in Picnic at Hanging Rock; Laura is the homecoming queen living a double life, whose murder is at the heart of Twin Peaks; and Lux is one of the five mysterious Lisbon sisters who take their own lives, one by one, in The Virgin Suicides.

They’re girls on the cusp of adulthood—and the void. All three are testing their own growing powers (of beauty, sensuality, autonomy) while brushing up against frightening forces beyond their control or comprehension. They are worshipped, adored, rendered abstract and unreachable even when standing directly in front of their admirers. But this deification ultimately distorts their humanity and obscures their pain—leaving them vulnerable to violence, whether at their own hand or another’s.

Miranda St. Clare is the most enigmatic of the three; we barely glimpse her before she’s gone. Because of this, it’s hard to know who she really is, or her state of mind before her disappearance—was she suffering? Discontent? It doesn’t seem like it, but we’re also shown through the experiences of other students that Appleyard College’s strict Victorian values can be wildly damaging. In any case, I want/choose to believe that Miranda had some sort of agency, or at least acceptance, around her disappearance. To me, it wasn’t so much a violent spiriting away as a welcome ascension.

This is hinted at by a couple cryptic lines early on. When her classmate Sara Weybourne becomes so overcome with emotion for Miranda that she can hardly speak, Miranda tells her gently: “You must learn to love someone else, apart from me. I won't be here much longer.”

And later: “Everything begins and ends at the exactly the right time and place.”

Did Miranda predict her own disappearance? Did she go to Hanging Rock with the intention to cross a threshold? As Sarah says: “Miranda knows lots of things other people don’t know.” Is that alluding to some preternatural knowing, or simply the confidence of someone who understands how to use her beauty to bend the world in her favor?

The latter is exemplified at the titular picnic at Hanging Rock, when she sweetly convinces her chaperones to let her and a few other girls to climb the formation, which they’ve been explicitly forbidden to explore. Instead of being frustrated by Miranda’s rebellious request, her teacher not only concedes, but gazes in awe as she walks away, calling her a “Botticelli angel.”

We see Miranda’s journey right up until her disappearance—leading her friends higher and higher through wind-whittled canyons, shedding their black stockings and shoes, and occasionally collapsing, before waking again and pushing forward. The entire time they seem at the mercy or compulsion of some vibrating, energetic force, but Miranda shows no fear.

Ultimately, Miranda seems to fulfill the archetype of the precocious and jaded teenage girl who has outwitted the adults around her, and must now flirt with forces beyond her comprehension in order to feel alive, challenged, or aroused. And so she walks on, deeper into the void, shedding her Victorian undergarments one by one—a borderline erotic act of liberation.

Later in the film, one of Miranda’s comrades is found by a lovestruck boy who saw the girls hiking. Irma, whose brown coif and arch line delivery reminded me of Twin Peaks’ Audrey Horne, has no memory of what happened to her or her friends. She’s covered in mysterious bruises but otherwise is “intact,” in the words of the local doctor.

The image of Irma recuperating after her rescue immediately reminded me of another brunette from Twin Peaks—Ronette Pulaski, who survives the attack that ended Laura Palmer’s life.

The doctor also notices that Irma’s worst injuries are on her hands. In Twin Peaks / Fire Walk With Me, the police find small pieces of paper with various letters on them shoved under the nails of Ronnette, Laura, and Theresa Banks, who all worked at the same brothel and were targeted by the same killer.

Picnic and Fire Walk also feel very spiritually similar to me because of the sense of the supernatural that vibrates through both films.

Consider their locations: a British colony in Victorian-era Australia, and a small logging town in Washington state, both areas that were once home to large Indigenous/Aboriginal populations.

Hanging Rock is a real geological formation in Victoria, Australia that was occupied by the Dja Dja Wurrung, Woi Wurrung and Taungurung tribes and was considered spiritually significant. While Twin Peaks is a fictional town, it was filmed near Snoqualmie, Washington and heavily features shots of Snoqualmie Falls, which is considered a sacred site by the Snoqualmie tribe.

Both films suggest that the land holds a power that refuses to be erased; that a force is always alive beneath the surface, perennial and waiting. Hanging Rock is shot as a towering, looming entity with an almost gravitational pull, and every visual of it is paired with eerie sound design. It is not something to be mastered or mapped; it is something that devours. Under its spell, the girls slip into something (or somewhere) that predates them and will outlast them.

In the Twin Peaks universe, Ghostwood National Forest literally houses a portal to a different dimension: the Black Lodge, a room that functions outside of linear time and space and is inhabited by evil beings. As one character warns Agent Dale Cooper: “The woods are wondrous here, but strange.” Within the cosmology of Twin Peaks, the entities in the Black Lodge feed on garmonbozia, a substance that embodies “pain and sorrow.” In this universe, trauma isn’t just experienced; it is harvested, and Laura Palmer is one of their most potent sources.

While the TV series introduced Laura as a memory and a myth—the dead homecoming queen wrapped in plastic—Fire Walk allows her to be fully, frighteningly human. It takes us so deeply into Laura’s specific pain that it’s often unbearable to witness.

To the outside world, Laura is loyal friend and do-gooder who volunteers for Meals on Wheels and dates a football star. But privately, she has been suffering sexual abuse at the hands of BOB, a supernatural entity from the Black Lodge, every night since she was 12. As Laura discovers halfway through the film, BOB actually carries out his torture by possessing her father, Leland, who acts on his behalf. She is also sex trafficked by her employer, who has created a pipeline of young girls working at his department store’s perfume counter to his brothel across the Canadian border.

We see the incongruity between Laura’s reputation and her reality eat away at her and fracture her identity. She dissociates through cocaine and sex with strangers she picks up at the Bang Bang Bar. And she convinces herself there’s no one she can confide in, even her best friend Donna (whose affection for Laura has a distinct sapphic undertone that I don’t remember in the TV show, but feels undeniable here).

When her lover James, tries to intervene, she admonishes him: “Quit trying to hold on so tight. I'm gone. Long gone. Like a turkey in the corn.” Here, her “prediction” doesn’t come across like some preternatural foresight—it’s a statement of resignation, the result of bone-deep fatigue.

Laura is embodied with operatic perfection by actress Sheryl Lee, who was originally hired by director David Lynch to simply play Laura’s dead body on the TV show. He soon recognized her as a special talent who could hold her own next to other rising stars in the cast, and her skill is never more evident than in this movie (many Lynch devotees think she was robbed of an Oscar nomination).

Sheryl Lee wrote a letter to Laura after she finished filming:

“The thing I remember most about you, though, Laura, is your loneliness. That loneliness haunted me. Walking back into my empty hotel room by myself each day, left to deal with the fragmented pieces of my own life, your loneliness would still fill my room. My prayer is that you are now someplace where you are truly loved and at peaceful rest.”

More than either of the other girls, I believe that Laura wanted to live. Her death—she is murdered in those woods by her (possessed) father—was not a choice, was not peaceful, was not defiant. But it’s only in death that Laura can truly find relief. And unlike the other girls, we get to see what happens to Laura afterwards: she appears in the mystical Black Lodge, welcomed by a glowing angel, and breaks out into laughter, finally free.

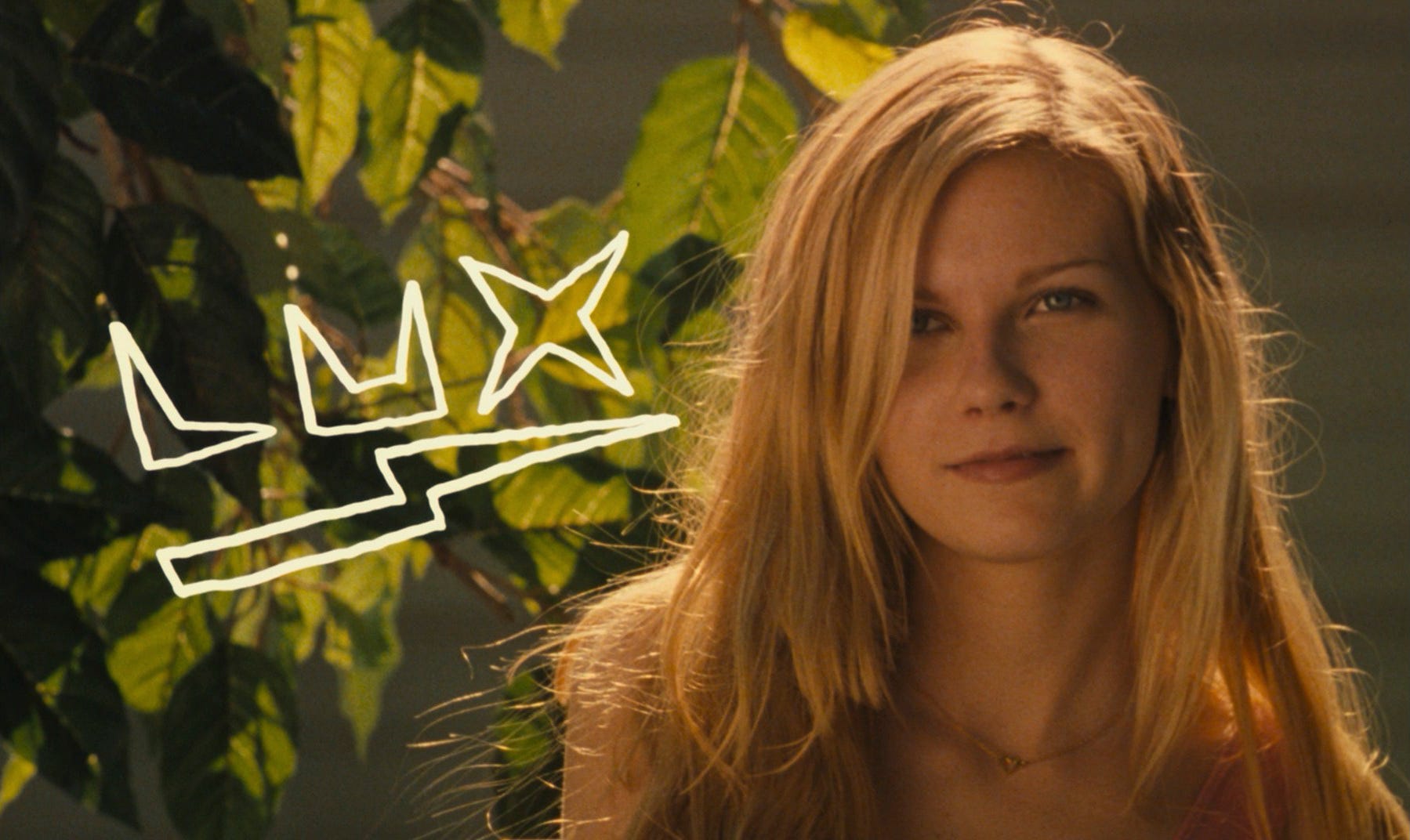

Like Laura, fourteen-year-old Lux Lisbon’s chance at a fulfilled, happy life is thwarted by the very people meant to protect her. Though the Lisbon sisters are treated with a mystical reverence by the gaggle of teenage boys who obsess over their every move, in reality, they are withering under the thumb of their strict, Catholic parents.

After the youngest Lisbon sister, Cecilia, kills herself by jumping out her bedroom window and onto a fence, the Lisbon parents tighten their vice grip even further, becoming paranoid and reactive. Their daughters all feel smothered, but none more than Lux, who is the most sexually curious, and has the school heartthrob wrapped around her perfect finger. She finally loses her virginity to him after the homecoming dance, but she wakes up alone on the football field the next morning.

As a result of missing her curfew, her mother resorts to her most extreme punishment yet—she pulls all of the girls out of school and forces Lux to burn her vinyl records in the fireplace. In isolation, the girls wilt even further: “The color of their eyes was fading along with the exact locations of moles and dimples. From five, they had become four, and they were all the living and the dead, becoming shadows.” Soon after, Therese, Mary, Bonnie, and Lux all take their lives in one night, leaving the besotted neighborhood boys to find their bodies.

Unlike Leland/BOB, who systematically tried to break Laura’s spirit, the Lisbon parents truly thought they were acting in the best interest of their children.“None of our daughters lacked for love,” says their mother. “There was plenty of love in our house. I never understood why.” Though The Virgin Suicides lacks the supernatural element of the other films, that line feels chilling, because it reflects the friction and fundamental misunderstanding that exists between so many parents and their children. This is an extreme case—but I’d venture that anyone who was once a teenage girl would have little trouble putting themselves into Lux’s headspace, and understanding her sense of suffocation and hopelessness. And Mrs. Lisbon’s lack of accountability or self-awareness is also its own kind of horror.

At least Miranda and Laura’s deaths sent their small, insular towns into turmoil, catalyzing a collective soul searching and shattering the communities’ carefully maintained illusions. More death followed their disappearance; nothing was ever the same. In Grosse Pointe, the Lisbon sisters’ deaths are first treated as fodder for the local news cycle. Reporters flock to their lawn; the neighbors rubberneck and gossip. And one year after the Lisbon parents finally move out, it’s decided that the theme of the upcoming debutante ball will be “Asphyxiation.” Lit by sickly green light, partygoers wear gas masks and fake deadly falls into a swimming pool. Not content to simply forget the girls, the town turns them into a punchline, and dances on their grave.

Well…

That’s probably enough for now. But since this is the debut of Film Miroir, I’ll end with a collection of ~mirrors~ from these three films.

obsessed w you

I've always likened Picnic at Hanging Rock to a cosmic horror film. There's something so otherworldly about every frame and sentiment shared in that setting. Great essay!